FU: Non-Insularity

This one character, the FU of FUKAN-ZAZENGI, has in itself very profound and great meaning. Even to have met just this one character, somewhere in a past life in between the cheating and lying, pimping and prostituting, wanking and worrying, I must have done something good.

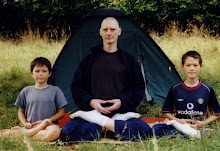

Sometimes when I am in France (at time of writing I am back in England in pre-dawn insomnia mode) the sights or sounds or general energy of the forest sweeps away a surface layer of my habitual unenlightened concern with small matters -- for a while. That is my inspiration for discussing One Love (see also photo added to previous post), together with an email exchange with an old friend.

This old friend is the bloke who first shaved my head 20-odd years ago and revealed me in his words to be Cro Magnon Man. I called him a "stateless seeker of One Love." "Stateless" because though nominally American he went to school in the Middle East and in many ways he is more Japanese than American. And yet he is in no way Japanese. He is the person who taught me the fundamental rules of Japanese behaviour, while always demonstrating in masterly fashion how to skirt or flaunt those rules. "Seeker of One Love," partly because he has been a lifelong fan of brother Bob Marley, whom he knew for a time, not quite in a biblical sense, but in a very intimate way -- and he has the photos to prove it. But beyond the Rasta concept of One Love (which in itself might be of dubious universality rooted as it is in the old testament) Stateless Seeker looks for One Love in nature, and especially in the sea. "Everything goes in waves," he taught me, long before I had heard of the 2nd law of thermodynamics.

Stateless Seeker once described himself to me, in a phrase that stuck in my mind, as "just another nigger in the trenches." The phrase resonated with my own sense of coming from a downtrodden background. My mother, whose father ran away, was brought up mainly by her maternal grandparents, a cotton mill worker and a labourer in a Lancashire paint factory. My father was the son of a South Wales steelworker who in turn was the son of a poor Irish immigrant mother, Gran Cross, who after a coal mining accident in around 1910 was left a widow with an 11-year old son and seven younger siblings to bring up.

On the other hand, that 11-year-old grew up to be Sir Eugene Cross, a decorated war hero in WWI and leading light in the South Wales labour movement. And my parents were both bright sparks who went to grammar schools and ended up at Birmingham University where they met each other and -- at the very moment of losing their virginity to each other -- conceived yours truly, a big mistake from the very outset. By the time I was born on Christmas Day 1959 my 21-year-old father had been booted out of university and had got a job at the Austin factory at Longbridge. My memories of early childhood are coloured by Sundays in which the housekeeping money had run out and there was nothing in the pantry to eat. This may be why I continue to find it difficult not to be tight with money, and I worry about money, whether I have reason to do so or not. Sometimes I find it difficult to charge the going rate for professional work, and I charge people too little. Ironically, I charge them too little not because I don't care about money, but rather because I care about money too much. (A friend who worked in the city in Tokyo once told me that the guys who made the really big bucks were able to do so because they didn't care too much about money. They were thus able, with brass balls, to negotiate ridiculously big pay packets.)

Anyway, the point I am trying to make is that I came out of poverty, out of a long line of nobodies, but it was an educated or enlightened poverty out of which Uncle Eugene, a Big Somebody, Mr Ebbw Vale, had risen. And I ended up passing an exam to go to what was regarded as the posh school in Birmingham, where it was drilled into us that we belonged to a privileged elite. So all this is a kind of socio-economic attempt to excuse myself for being petty-minded, money-grubbing and elitist -- while at the same time having empathy for downtrodden underdogs everywhere.

Besides that, there is the cultural aspect, shared with other Brits and with Japanese too, of being brought up in an island nation. With that goes a similarly paradoxical combination of insularity, and irrepressible interest in the wider world.

Again, there is the religious/emotional aspect of having been brought up to believe in universal Christian values, and then enduring the shock of finding myself alone in Japan, bemusedly separated from my supposed soul-mate and living as a registered alien. Morever, for most of those years, through the economic bubble of the 1980s, the philosophy that was in the ascendancy in the Japanese media was NIHONJIN-RON, "Japanese-ism." When I attended Gudo Nishijima's Japanese lectures during the 80s, I would often hear him loudly singing out the words WARE-WARE. WARE-WARE this. WARE-WARE that. WARE-WARE simply means 'we,' but it very often appears in the nationalistic/racist context of WARE-WARE NIHONJIN, "we Japanese."

"Buddhism," Gudo would pontificate in English, "is an international religion."

No, you stupid so and so, the Buddha's teaching is not an -ism, and it is not an international religion. It is a universal teaching.

Is sitting-zen a gift to be bestowed from enlightened Japanese civilisation centred on practical, realistic doing, down to an unenlightened, barbarian world divided and ruled by the dualistic caucasian intellect?

No, it is not that.

If it is anything, it may be the true practice and experience, far beyond the bankrupt Rastafarian concept, of One Love.

It may be that when, through not taking too seriously the most serious thing in the world -- i.e., the inhibition of petty-mindedness, meanness, insularity, elitism, nationalism, racism, and all other forms of unenlightened behaviour -- a person truly realizes that One Love roundly pervades all, then the first thing which spontaneously expresses itself is universality.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home