Sunday, November 25, 2007

Ma-Ma Mantra

Oh marion, oh marjory

Om mani padme hum.

Oh marion, oh marjory

Who loved me like my mum.

That womb-like state of ease and grace,

The gaa gaa goo of tit on face,

I instinctively expect.

But in just sitting, at this place,

In thinking upward, from this base,

All learn the backward step.

So burglar, fraudster, pimp and whore,

Whose birthright is not mine:

On a hundred thousand sitting floors

Let's turn the light and shine.

Om mani padme hum.

Oh marion, oh marjory

Who loved me like my mum.

That womb-like state of ease and grace,

The gaa gaa goo of tit on face,

I instinctively expect.

But in just sitting, at this place,

In thinking upward, from this base,

All learn the backward step.

So burglar, fraudster, pimp and whore,

Whose birthright is not mine:

On a hundred thousand sitting floors

Let's turn the light and shine.

Saturday, November 24, 2007

Friday, November 23, 2007

OYOSO TOSHO O HANAREZU

"In general, it does not leave this place."

TOSHO means this place, or this moment in time.

This place, or this moment in time, is the instant that a stimulus to activity is reaching our consciousness. In working on the self, it is the only instant that has any value whatsoever.

This teaching was a particular strong point of Gudo Nishijima, who, like many Japanese people I met in Japan, manifested an enviable and seemingly inherent ability to live in the moment of the present. I was aware of this, for example, when a telephone call would interrupt our work in his office. Full attention would be given to the telephone call, after which our work would be resumed, often in mid-sentence, as if the telephone call had never existed.

Marjory Barlow in contrast described herself, as she described me, as "an inveterate worrier." Living in the moment, i.e. not endgaining, was something that she had spent a lifetime consciously working at, indirectly. Her aim was always to bring her pupil in time with the moment of the present, although she never verbalized that aim to me. (She verbalized it in her book, to Trevor Allan Davies.) What she verbalized to me was mainly these directions: "Let the neck be free, to let the head go forward and up, to let the back lengthen and widen; sending the knees away from the hips, pulling to the elbows and widening across the upper part of the arms, as you widen the back." She verbalized those directions and clearly impressed on me that I was not to react to those words in my habitual way, by feeling/doing something partial and specific.

The indirect effect of being led into the space between listening to those verbal directions, and not doing them, was an opening of the innermost ear to the singing of birds, and to the silence in between sounds of traffic in the distance.

In her talk which is reproduced in full on my webpage, Marjory traces FM Alexander's investigative process, from his initial premise that he must be losing his voice because of something he was doing to himself, through backward step after backward step, until he reached the innermost point where he found his wrong doing could be stopped.

"Alexander could not change anything by doing. He could not trust his feeling. He then saw that he had underestimated the strength of habit. What he observed in the mirror was the end-result of disordered patterns lying deep in the nervous system. And that these inner patterns of impulses, conveyed through the nervous system to the muscles acting on the bony structure and joints of the body, were operative perpetually, whether he was moving, speaking or sitting still. In fact these inner patterns were him -- insofar as his body was the outer manifestation of them. The next step in the journey was taken when Alexander realised that the only place where he could begin to control the wrong habitual patterns was at the moment when the idea came to him to speak or move. The moment when, whatever state of misuse he was in, would be made worse as he went into action. He had reached the only place, and the only moment in time, where change could begin, or where he could have any control over the habitual patterns of misuse, which were dominating everything he attempted to do. This place, or this moment in time, was the instant that a stimulus to activity reached his consciousness. In the ordinary way, when a stimulus comes, we react to it in the only manner possible. The response is made without thought -- without any knowledge on our part of what we are putting into motion. The reaction is the immediate response of the whole self, according to habitual patterns of movement which we have developed from our earliest years. We have no choice in this, we can behave in no other way. We are bound in slavery to these unrecognised patterns just as surely as if we were automatons. When Alexander reached understanding of this part of the problem he had found the key to all change. He understood at last in what way he must work. We have now followed him in his journey from the outermost manifestation of misuse, that is the interference with the normal working of his whole body, resulting in the vocal failure, to the innermost point where he could stop this interference."

Sitting-zen is the truth itself. Marjory's teaching was the truth itself.

The truth of sitting-zen and the truth of Marjory's teaching are not two truths. If a person says that it is wrong to identify Marjory's teaching with the truth of sitting-zen, it may not only be that the person has not appreciated the truth of Marjory's teaching; it may also be that the person's sitting-zen has not yet got to the bottom of the truth of sitting-zen.

For anybuddha whose sitting-zen has already got to the bottom of the truth of sitting-zen, there is no need at all to read Marjory's words -- although it might be natural for such a person to be interested in Marjory's words.

For anybody whose sitting-zen has not yet got to the bottom of the truth of sitting-zen, as manifested in unwholesome teachings like pulling in the chin, there may be something still to investigate in Marjory's words.

Thursday, November 22, 2007

TARE KA HOSSHIKI NO SHUDAN O SHINZEN?

"Who could believe in a means of sweeping?"

"The whole body is out by far of dust: who could believe in a means of sweeping?"

Marjory Barlow would sometimes recommend to her pupils the practice of looking in a mirror. The point of this practice was neither to get rid of any dust on the mirror nor to get rid of any postural imperfections or facial asymmetries reflected in the mirror. The aim of this work was simply to look, just to observe. "Simply to look" means to look without endgaining. "Just to observe" means to observe without endgaining. Not endgaining means, in other words, inhibiting concern with specific, superficial, peripheral things, so as to allow the possibility of something more real and whole emerging from deeper within.

Similarly, the vital art of sitting-zen, which Master Dogen described as forgetting peripheral things and naturally becoming one piece and, equally, as non-thinking, has to do with giving up endgaining and thereby allowing our original features to emerge, as they are, in total, warts and all.

About 20 years ago my teacher Gudo Nishijima said to me, very strongly, when I recommended him to get off his high horse: "I have to keep my position, in order to save all people in the world."

Thus I served the pompous little bastard, believing him to be a big strong bloke motivated primarily by the will to the truth. But after I began to understand, and began to tell him the truth about his misguided endgaining method of trying to correct people's posture with his hands, the pompous little bastard showed what a pompous little bastard he truly was. The pompous little bastard could not tolerate his own mistake.

When in a dusty mirror a totally pompous little bastard looks at a totally pompous little bastard, the difficult thing is just to look.

Wednesday, November 21, 2007

ZENTAI HARUKANI JINAI O IZU

"The whole body is out by far of dust."

Despite feeling a tad rough this morning -- as a result of unwholesome conduct committed by me, stemming from greed, anger and delusion, and performed with body, mouth and mind, all of which I now confess and regret -- I shall press on regardless.

In this introductory section of his Rules of Sitting-Zen for All, Master Dogen is still expressing his great realization that there is nothing for us to do, because the right thing does itself, the truth is inherent in us and our surroundings, Time's Arrow is already pointing everything in the right direction. Originally, all is whole.

The very word ZAZEN, sitting-zen, is just an expression of this great realization.

My first contact with Gudo Nishijima was as a result of me finding in a bookshop in Okinawa his book "How to Practise Zazen." Presumably it was because Gudo was not sufficiently versed in the use of the hyphen in English, because he didn't realize that he could use a hyphen to make sitting-zen into one word, that he left the word Zazen untranslated. Rather than go down the palpably false path of separating sitting-zen into "seated meditation" or some such travesty, Gudo followed the Olde English principle of If in doubt, do nowt. He left ZAZEN as Zazen. The person whose job it was to translate ZAZEN as sitting-zen, or sitting-dhyana, was me. But I didn't do it. I blew it.

It matters a lot, because, in the absence of sitting-zen or sitting-dhyana, people have started to use "seated meditation," which fosters a misconception about what sitting-zen is. Either that or they go on about practising ZAZEN, thereby dumping sitting-zen in the skip labelled "mystifying Japanese words," alongside not only traditional terms like JUKAI (receiving the precepts), ANGO (retreat), and HOSSU (whisk), but also spurious innovations like KYOSAKU (stick for whacking people on the shoulder) and SESSHIN (intensive practice period). People seem to like using those Japanese terms as if the Japanese terminology lent credibility to their practice. When I see that tendency I feel angry with myself. Because that tendency also exists in me, I remained blind to the fact that my single most important job as a translator was to translate ZAZEN as sitting-zen or sitting-dhyana. But I didn't do it. I blew it.

The sitting-zen of Master Dogen was never intended to be unwholesome. But "seated meditation" definitely tends towards the unwholesome.

To sit is the Buddha-Dharma and the Buddha-Dharma is to sit. To sit is wholesome.

To practice seated meditation is not wholesome. To practice seated meditation does not accord with the truth that the whole body is out by far of dust.

Similarly, to practice SHIKAN-TAZA is not necessarily wholesome. SHIKAN-TAZA means just sitting. Just sitting just means to sit. But we tend not to understand it like that. We don't just sit, in a wholesome manner. We conceive of something called SHIKAN-TAZA, involving pulling the chin into the neck et cetera, and we practice it willfully. We turn SHIKAN-TAZA into an end, and we practice endgaining, which tends not to be wholesome.

Endgaining is not necessarily unwholesome. When buddha goes directly for an end, no harmful side effects are generated in the process.

But if our underlying conceptions are false and if the vestibular functioning which is the foundation stone of human living is imperfect, then endgaining results in unwholesome conduct -- as a result of which, after a time lag in the short, medium, or very long term, a person is liable to wake up feeling rough and thereupon to lumber wearily towards his sitting-cushion, sadly lacking in the exuberance department.

Tuesday, November 20, 2007

NANZO KUFU O TSUIYA SAN?

"Why expend effort?"

Master Dogen is denying a particular kind of effort; namely, the effort of wrong doing which stems from an endgaining idea.

Alexander Technique teacher Patrick Macdonald wrote:

"In learning the Technique considerable effort on the part of the pupil is required. A first step is to learn what sort of effort is necessary. The first essay nearly always produces more muscular tension, particularly in the neck, and this is exactly the opposite of what is required. The pupil must learn to stop doing, "to leave himself" in the hands of the teacher, neither tensing nor relaxing. Further, any emotional involvement in trying to learn what to do, or in what is going on, should be avoided. The best results are gained when a pupil can disassociate himself from what is happening, as if he were standing on one side watching someone else being taught. If he can do this for a time he will find himself taking his proper part in the process, with an awareness that is quite different and greatly enhanced. Alexander named the opposite of this kind of behaviour 'endgaining' (i.e. the desire to bring about the end in view, however wrong the means might be)."

Macdonald also wrote, probably as a result of reading Herrigel's book Zen in the Art of Archery:

"It is noteworthy that the Alexander Technique, like Zen, tries to unlock the power of the unknown force in man. Compare the Zen 'Let it do it' to Alexander's 'allow your body to work as Nature wishes.' The techniques for bringing this about are, no doubt, different."

It is interesting that Macdonald saw this parallel. But the Zen of Archery, the Zen of which Herrigel wrote, is Soto Zen, or Rinzai Zen. It is the Zen of Zen Masters, it is the Zen of Zen Mind, Beginners' Mind, it is the Zen of Zen gardening and Zen temples. It is the Zen of the Zen koan. It is the Zen of Zen meditation. It is not the sitting-zen of Master Dogen.

If there are two different techniques, a Zen technique and an Alexander technique, I am not aware of either of them. What I am aware of, both in my sitting-zen practice and in giving or receiving hands-on Alexander work, is the choice of going in one of two directions.

The first direction, my habitual one, is forward. Forward where the knocks are hardest, Some to failure some to fame, Never mind the cheers or hooting, Lower your head and, with grim determination and enormous effort, play the game.

The alternative direction, the opposite one, is backward. This latter direction also requires effort, but it is not effort to realize an endgaining idea; it is rather effort in exactly the opposite direction. It is effort not of doing but of learning, but not the kind of learning that goes on in school. EKOHENSHO NO TAIHO O GAKU SUBESHI. "Learn the backward step of turning light and luminescing." It is an effort not to achieve but to allow: to allow a spontaneuos flow of energy which can begin to happen when an endgaining idea is given up, or inhibited.

When my wife and I met, in our late 20s, we were both into gym work. We met in the gym of a sports club which she was managing. So were both quite muscly and at the same time quite stretchy, as a result of lifting weights, stretching, running, swimming, et cetera.

Despite all this athletic effort, I had notoriously cold feet. On one winter evening my then karate teacher Sensei Morio Higaonna pointed at my purple toes and said with a greatly amused chuckle: MIKE! CHI NO MEGURI GA WARUI NE? -- literally, "Mike, your blood circulation is poor, isn't it?" I wondered why my teacher had found this observation so amusing. Later I understood that to have poor circulation means, metaphorically, to be slow on the uptake.

But last night as I lay in bed watching my favourite Newsnight presenter, the master of intolerant grouchiness Jeremy Paxman, my wife interrpupted my viewing by saying, "Mike, your feet are so warm!"

Ha! Ha! Ha! The race is not always to the swift.

Sunday, November 18, 2007

SHUJO JIZAI: The Fundamental Vehicle Naturally Exists

In other words, the right thing does itself.

When released, twisted fibres naturally tend to unwind....

As long as it is not deprived of air, the stick of incense naturally tends to keep burning down, towards the earth.

As long as it is not deprived of sunlight, the non-sentient being naturally tends to grow upward, towards the heavens.

Master Dogen's words SHUJO, fundamental vehicle, as I understand them, have to do with the inherent tendency that energy has -- via such processes as muscular release, respiration, digestion, and growth of living things -- spontaneously to flow (see, for example, www.entropysimple.com).

FM Alexander said that change was the ultimate reality. It wasn't a parrotted idea that FM had picked up from some sutra: it was a realization that followed from his own independent learning of the backward step of turning light and luminescing.

The fundamental vehicle naturally exists. It is not a realization that anybody can teach to anybody.

IKADEKA SHUSHO O KARAN?

"How could it borrow from practice and experience?"

"Upon investigation, um, enlightenment roundly pervades: how could it borrow from practice and experience?"

Even when going for a literal translation, there is not a definitive one that deserves to be set in stone. And even less can there be a definitive explanation of the meaning of each sentence.

That is partly why I have gone through the original version of Fukan-zazengi character by character on my webpage, and I would encourage anybody who is interested enough to read this blog, to follow the link on the right of the page and start the process of getting Fukan-zazengi straight from the horse's mouth.

If as a result of that process, you would like to publish on this blog your own translation or interpretation of any line, or any section, of Fukan-zazengi, then please be my guest.

But if I write here what the above characters are saying to me, on this particularly auspicious morning, they are saying what Marjory Barlow said the first time I heard her speak:

This work, this business of working on the self, is the most serious thing in the world. But you mustn't take it seriously.

Every day for the last 25 years when I wake up in the morning I have woken up with the idea already there in the back of my mind that the most important thing today is my own sitting-practice -- as if everything in the Universe depended on it. In a sense, everything does. But in another sense my own anxious self-consciousness about the great importance of my own practice, is laughable. I am no different from the teenager I was on the bus, struggling through body-building, affected Brummie accent, and various other contrivances, to rise above his own self-conscious insecurity... "There goes that wanker again."

Master Dogen writes that sitting-zen is the practice and experience that gets to the bottom of the Buddha's enlightenment (BODAI O GUJIN SURU NO SHUSHO NARI).

A problem arises in my habitual reaction to that idea. Even though I don't know what enlightenment is, I believe in the Buddha's enlightenment as a historical fact and I want to get it myself, without counting the cost. As sitting-zen is the practice and experience that penetrates the Buddha's enlightenment, and the only person whose sitting-zen I can practice and experience is my own, my own practice and experience of sitting-zen must be the most important thing there is.

The reasoning here is not at fault. The reasoning is impeccable. The fault, the flaw, the taintedness, lies in my habitual reaction to an idea. The fault lies in the endgaining. The fault lies in my habitual attitude of unstinting grim determination to solve a problem.

If I wake up in the morning and succeed in inhibiting my self-important idea, and as a result go back to sleep until 9 o'clock, thereby losing time that could have been devoted to the practice and experience of sitting-zen, it is not the end of the world.

Saturday, November 17, 2007

ENZU: All-Round Pervading

Correct me if I am wrong but I remember hearing somewhere that Louis Armstrong said, when somebody asked him what is Jazz, "If you've got to ask the question, you'll never know!"

The question I am asking now is this:

What is the relation between the FU (everywhere) of FUKAN-ZAZENGI, and this ENZU (all-round pervasiveness)?

Does anybody feel a dissertation coming on for a Ph. D in Buddhist studies?

TAZUNURU NI SORE: Investigating Um

For a wanker starting to get the real thing, it may be important to study the meaning of foreplay. Even after many years of getting the real thing, wankers everywhere are liable to find it impossible to prevent ourselves from going directly to the target. Going directly to the target has always been a forte of the wanker who is writing this blog.

Going directly to the target is another way of saying endgaining. Endgaining is the attitude of a person whose gaze is fixed narrowly upon the end of the road, without wider appreciation and enjoyment of the flowers, and weeds, that may be growing by the wayside.

What the endgainer is prone to forget is that getting to the end of the road is only an idea in his brain, whereas the flowers falling and the weeds sprouting by the wayside are real manifestations of the law, here and now.

Ultimate reality might exist in, er, um.

Yesterday on Desert Island Discs I heard of Chinese schoolchildren digging up flower beds because Chairman Mao regarded growing flowers as a bourgeois affectation. What a monster! At the same time, I know where he was coming from. He might have been a man after my own heart.

The British voter being as he or she is, and the British political system being as it is, with all its loveable inefficiencies and idiosyncrasies and anachronisms, we are unlikely at least in the foreseeable future to be lorded over by any overtly monstrous end-gaining tyrant like Mike Cross or Adolf Hitler or Chairman Mao. We are more likely to vote in the likes of a master of modest expression like, aw shucks, Tony Blair; or a bumbler like, um, er, Boris Johnson. Boris of course is a classics graduate, a student of Roman orators, who in their turn might have known a thing or two about rhetorical foreplay.

Friday, November 16, 2007

GI: Rules

In Alexander work, the decision not to do is fundamental. One of the most important things not to do is unduly stiffen the neck. With this in mind, Alexander formulated the verbal direction "to let the neck be free." But, as Alexander well understood, a verbal direction is a dangerous thing. When we hear a word, no sooner have we heard it than we have reacted to it by doing something -- so that, in making the decision not to do, something is unconsciously done. For example, the neck stiffens.

Some Alexander teachers, mindful of the difficulty of not doing the direction "to let the neck be free," use a wide vocabulary of other words to impress upon self and others the importance of not doing the direction -- allowing the muscles of the neck to release, thinking of space, et cetera, et cetera.

But Marjory Barlow would sometimes command me, in quite a fiesty manner, "Now, free your neck." It sounded like she was ordering me to do something. But I knew she didn't want me to do anything. And that was just Marjory's point. Rather than try to spoon feed me, Marjory was giving me the stimulus and asking me to work out for myself the non-response, begining with my decision not to do the direction.

This is all by way of preamble to discussing the final character in the title FUKAN-ZAZENGI, and that is this one, GI:

GI means rule.

If you don't like the sound of it, that's your problem. Get over it.

The problem, in other words, is not in the word but in your reaction to it.

GI means rule.

FREE YOUR NECK!

Wednesday, November 14, 2007

ZAZEN: Not Zazen

Gudo Nishijima made a complete horlicks of translating Shobogenzo into English. While realizing, as his student, that I had to redo the whole thing from scratch, in some ways I failed in that task. I left in tact some Gudo-isms that I should have questioned more extensively. The best example of my stupidity as a translator was leaving the translation of ZAZEN as "Zazen" -- what kind of translation is that?

ZA means to sit. There is nothing mystical about ZA. It is a simple verb: to sit.

ZEN represents the sound of the Sanskrit word dhyana.

So the literal translation of ZAZEN is sitting-zen or sitting-dhyana. There is no difficulty about it. If you want a totally English translation, then it might be sitting-meditation.

What possible reason is there for leaving ZAZEN untranslated as "Zazen"? Does using the Japanese word ZA instead of the English word "sitting" lend a sound of greater authenticity? If you continue to think so, you are even more of a wanker than I was.

Here is a short koan to underline the point:

A Soto Zen monk says to a non-Buddhist non-monk:

"I am a Zazen monk of the Soto Zen church."

The non-Buddhist non-monk remains silent.

(But secretly to himself he is thinking: "You are a wanker.")

If you check out the internet writings of some of Gudo's Dharma-heirs you may find translations of ZAZEN that are much worse still than "zazen."

On James Cohen's webpage for example I found the words "seated meditation." Similarly on Eric Rommeluère's webpage in French I found "méditation assise."

Those translations have merit in the sense that they are translations; they are oriented in the direction of de-mystification. However, they reveal a total lack of understanding of the fundamental point of Master Dogen's sitting-zen. More than that, they reveal a total lack of understanding of the fundamental point of the stupid Zazen of Gudo himself -- for whom Zazen has got nothing at all to do with meditation, but is just to do the act of sitting.

I do not know what sitting-zen is. But if there is any Zen Master out there who, notwithstanding the clarification I have just made, would like to persist in translating ZAZEN as seated meditation, or méditation assise, or meditacion sentada, or any similar two-word phrase, I would like to say without hesitation (but possibly with just a hint of Paul Whitehouse & Harry Enfield):

No, you fucking wanker. No, you rosy-cheeked, red-nosed clown. No you Zen fraud who does not even know that he is a fraud. No, it is not that.

Not seated meditation, you tosser. Sitting-zen.

FUKAN: Encouragement Everywhere (No Great Idea Anywhere)

Christmas Humphreys in one of his many books on Zen, Buddhism, et cetera, once wrote that there is nothing more powerful than an idea whose time has come.

If that is so, then any aspiring Messiah who wishes to save all beings in the ten directions, whether they like it or not, needs first and foremost a great idea whose time has come.

Once the great idea, the idea that can lead the world to progress into a new golden age, has been clearly understood, then can begin the progressive process of indoctrinating others.

I, mainly through my contribution to the Nishijima-Cross translation of Shobogenzo, have been instrumental in such a process.

Gudo Nishijima's big idea is realism. About 20 years ago he told me that he hopes that his idea will remain on the globe after his death. Since then, in his characteristic slow but energetic, resolute, and realistically manipulative manner he has been gradually working towards that end. That is what Dogen Sangha International is all about -- a means for keeping a great man's great idea alive after the man himself has died.

In indoctrinating others, that is, in convincing others of the validity of his great idea, the indoctrinator may exhort, persuade, urge, or prevail upon others. These are all translations of the character pronounced in its Chinese-sounding reading as KAN, or in Japanese as SUSUMERU.

Translations of KAN at the opposite end of the coercive spectrum include encourage, or offer up.

So what is FUKAN-ZAZENGI all about? Is it a tool in the armoury of a religious philosopher/indoctrinator with an agenda to leave his dirty imprint on the pages of human history? Or is it a kind of encouragement, a kind of agenda-free offering?

It seems to me that it can be either.

In going wrong, I have tended to see it more as the former. To the extent that I am able to glimpse my wrong tendency for what it is, I see it as definitely not the former.

It seems to me that Fukan-zazengi can be either, but it can never be both. It is one or the other -- either, or. Either it belongs to endgaining practice, or it belongs to non-endgaining practice.

'Master Dogen's Rules of Sitting-Zen are an expression of the great idea that can lead to salvation all human beings in the ten directions. I can make my own miserable life into a supremely valuable life by exhorting, persuading, urging, and prevailing upon everybody in the ten directions to study, understand, and follow in practice, this great idea -- which might be called "realism", or "balance of the autonomic nervous system." '

At the root of going wrong, when we investigate going wrong in detail, what is usually happening is an unconscious reaction to some such idea. That is what FM Alexander saw with brilliant clarity, and that is what his niece helped me to begin to see for myself.

The root idea does not have to be a Messianic delusion. It can be the idea of rising from a chair, the idea of moving a leg, or the idea of joining hands and bowing. It can be an idea that is intimately connected with, in the words of Maggie Lamb, "a strangled bollock" -- the idea that my voice should be heard; that others should heed my crying out in pain.

"Ideas can lead us," my Zen Master told me. Yes, Master, how true your words are: ideas can lead us to devote our lives to the building of an empire, ideas can lead us to manipulate others, ideas can lead us to throw away our own integrity and humanity. Ideas can lead us directly into hell.

In the original version of Fukan-zazengi Master Dogen wrote a sentence that is explicitly not an exhortation to embrace an idea, but is rather an encouragement just unworriedly to sit:

"Not having a single idea, sit away the ten directions."

.jpg)

Tuesday, November 13, 2007

FU: Not In Any Particular Direction

I haven't finished investigating yet Master Dogen's intention, after coming back from China at the age of 27, in writing this character:

The two elements of the pictograph are said to be a sound (top half) and the sun (bottom half). How does that come to indicate the meaning of "everywhere"? I don't know. Waves/pulses of energy radiating out imperceptibly in all directions, as sound from the sun? I don't know.

What I do sense is the intimate connection between Master Dogen's choice of this character and his outstanding bodhi-mind. His wish was that the truth of sitting-zen should radiate out in all directions, covering not only sentient beings of his own family, race, nation, or world, but sentient beings everywhere; and not only sentient beings but also the sun and moon, and every star in the night sky.

And this wish was not just a wishy-washy wish. Having thought out already what he wanted to transmit by writing the rules of sitting-zen, he took hold of a writing brush, dipped it in black ink, and concretely expressed his intention on a big sheet of paper, like this:

The two elements of the pictograph are said to be a sound (top half) and the sun (bottom half). How does that come to indicate the meaning of "everywhere"? I don't know. Waves/pulses of energy radiating out imperceptibly in all directions, as sound from the sun? I don't know.

What I do sense is the intimate connection between Master Dogen's choice of this character and his outstanding bodhi-mind. His wish was that the truth of sitting-zen should radiate out in all directions, covering not only sentient beings of his own family, race, nation, or world, but sentient beings everywhere; and not only sentient beings but also the sun and moon, and every star in the night sky.

And this wish was not just a wishy-washy wish. Having thought out already what he wanted to transmit by writing the rules of sitting-zen, he took hold of a writing brush, dipped it in black ink, and concretely expressed his intention on a big sheet of paper, like this:

Sunday, November 11, 2007

FU: Non-Sidedness

I love the fact that when the enlightened Dogen returned from China to his own narrow island, inhabited he thought by a small-minded people, the first Chinese character he wrote down in earnest was this one:

FU is the Chinese-sounding reading of the above character. The corresponding Japanese word that existed before Chinese characters were imported from China into Japan is AMANEKU. So if you look up this Chinese character in a Japanese-English character dictionary, it will be given as FU (Chinese-sounding reading) and amaneku (Japanese sounding reading).

AMANEKU means widely, extensively; far and wide; generally, universally; everywhere; throughout; all over.

Sometimes at the end of sitting practice, tentatively suspecting that there might have been some merit in the sitting we have just been practising, we express our exuberance by reciting out loud the following Japanese sentence:

NEGAWAKUWA KONO KUDOKU O MOTTE AMANEKU ISSAI NI OYOBOSHI, WARERA TO SHUJO TO MINA TOMO NI BUTSUDO O JOZEN KOTO O.

“I hope this goodness will spread to everybody everywhere, so that we and living beings will all together realize the Buddha’s truth.”

Everywhere is AMANEKU, that is, the FU of FUKAN-ZAZENGI. The meaning of AMANEKU is not this group, not that group; not our side, not the other side; not our friends, not our enemies; not self, not others; not the righteous, not the unrighteous; not Buddhist monks, not non-Buddhist non-monks: everybody everywhere.

Ten years ago my Zen teacher, Gudo Nishijima, observing my enthusiasm for the discoveries and work of FM Alexander, took a view of me as being a potential enemy of his “real Buddhism," and acted in accordance with his view, moving to protect our English translation of Shobogenzo from me who was translating it. One of the things that has impressed and inspired me over the ensuing years in which Gudo and I (in his words) have "crossed the Rubicon," has been the ability of one or two individuals among his students not to do the easy thing -- which would be to take the side of the perceived good shepherd against the perceived black sheep.

It seems to me, although this may seem fanciful, that this ability to remain impartial and unbiased is intimately related with a relative lack of attitude in a person’s sitting posture.

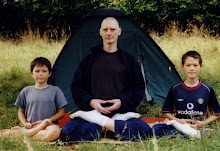

What does an open-minded, attitude-free sitting posture look like? I don’t know. But I know what a close-minded posture that is bursting with attitude looks like. I have got the photos to prove it -- of Mike Cross circa 1992.

When I google Fukan-zazengi, one of the first things that comes up is the commentary I wrote on Fukan-zazengi a few years ago that Eric Rommeluère published on his website (http://www.zen-occidental.net). I don’t know Eric personally, I haven’t met him face to face, but my impression of him, judging from his actions in conducting his website and from a bit of email correspondence, is of somebody open-minded who sees the Buddha’s teaching as a broad church, and equally somebody who is not burdened by particularly strong views on the importance of good posture.

People are prone to think that Alexander work entails learning a physical technique for maintenance of good posture. But nothing could be further from the truth.

In his fourth and final book FM Alexander wrote the following clarifying footnote:

‘When in my writings the terms “correct,” “proper,” “good,” “bad,” “satifactory” are used in connection with such phrases as “the employment of the primary control” or “the manner of use,” it must be understood that they indicate conditions of psycho-physical functioning which are the best for the working of the organism as a whole.’

FM was not talking about holistic hairdressing. He was talking about eradication of the end-gaining idea, about inhibition of unenlightened behaviour, about having no agenda, about non-sidedness. "People who have no fish to fry," FM used to say, "they see it all right."

Gudo Nishijima has suspected me of having my own egoistic agenda by which I would adulterate his own "real Buddhism" with my "Alexander theory." Is Gudo's suspicion valid? I don't know. How could I know? But if his suspicion were real, there would be a great irony in that. Why? Because the essential challenge, from whichever side we look at it, is to enjoy, in movement and in stillness, the ease and freedom which come from dropping off our own limited, partial, one-sided agenda.

NEGAWAKUWA KONO KUDOKU O MOTTE AMANEKU ISSAI NI OYOBOSHI, WARERA TO SHUJO TO MINA TOMO NI BUTSUDO O JOZEN KOTO O.

“I hope this goodness will spread to everybody everywhere, so that we and living beings will all together realize the Buddha’s truth.”

FU is the Chinese-sounding reading of the above character. The corresponding Japanese word that existed before Chinese characters were imported from China into Japan is AMANEKU. So if you look up this Chinese character in a Japanese-English character dictionary, it will be given as FU (Chinese-sounding reading) and amaneku (Japanese sounding reading).

AMANEKU means widely, extensively; far and wide; generally, universally; everywhere; throughout; all over.

Sometimes at the end of sitting practice, tentatively suspecting that there might have been some merit in the sitting we have just been practising, we express our exuberance by reciting out loud the following Japanese sentence:

NEGAWAKUWA KONO KUDOKU O MOTTE AMANEKU ISSAI NI OYOBOSHI, WARERA TO SHUJO TO MINA TOMO NI BUTSUDO O JOZEN KOTO O.

“I hope this goodness will spread to everybody everywhere, so that we and living beings will all together realize the Buddha’s truth.”

Everywhere is AMANEKU, that is, the FU of FUKAN-ZAZENGI. The meaning of AMANEKU is not this group, not that group; not our side, not the other side; not our friends, not our enemies; not self, not others; not the righteous, not the unrighteous; not Buddhist monks, not non-Buddhist non-monks: everybody everywhere.

Ten years ago my Zen teacher, Gudo Nishijima, observing my enthusiasm for the discoveries and work of FM Alexander, took a view of me as being a potential enemy of his “real Buddhism," and acted in accordance with his view, moving to protect our English translation of Shobogenzo from me who was translating it. One of the things that has impressed and inspired me over the ensuing years in which Gudo and I (in his words) have "crossed the Rubicon," has been the ability of one or two individuals among his students not to do the easy thing -- which would be to take the side of the perceived good shepherd against the perceived black sheep.

It seems to me, although this may seem fanciful, that this ability to remain impartial and unbiased is intimately related with a relative lack of attitude in a person’s sitting posture.

What does an open-minded, attitude-free sitting posture look like? I don’t know. But I know what a close-minded posture that is bursting with attitude looks like. I have got the photos to prove it -- of Mike Cross circa 1992.

When I google Fukan-zazengi, one of the first things that comes up is the commentary I wrote on Fukan-zazengi a few years ago that Eric Rommeluère published on his website (http://www.zen-occidental.net). I don’t know Eric personally, I haven’t met him face to face, but my impression of him, judging from his actions in conducting his website and from a bit of email correspondence, is of somebody open-minded who sees the Buddha’s teaching as a broad church, and equally somebody who is not burdened by particularly strong views on the importance of good posture.

People are prone to think that Alexander work entails learning a physical technique for maintenance of good posture. But nothing could be further from the truth.

In his fourth and final book FM Alexander wrote the following clarifying footnote:

‘When in my writings the terms “correct,” “proper,” “good,” “bad,” “satifactory” are used in connection with such phrases as “the employment of the primary control” or “the manner of use,” it must be understood that they indicate conditions of psycho-physical functioning which are the best for the working of the organism as a whole.’

FM was not talking about holistic hairdressing. He was talking about eradication of the end-gaining idea, about inhibition of unenlightened behaviour, about having no agenda, about non-sidedness. "People who have no fish to fry," FM used to say, "they see it all right."

Gudo Nishijima has suspected me of having my own egoistic agenda by which I would adulterate his own "real Buddhism" with my "Alexander theory." Is Gudo's suspicion valid? I don't know. How could I know? But if his suspicion were real, there would be a great irony in that. Why? Because the essential challenge, from whichever side we look at it, is to enjoy, in movement and in stillness, the ease and freedom which come from dropping off our own limited, partial, one-sided agenda.

NEGAWAKUWA KONO KUDOKU O MOTTE AMANEKU ISSAI NI OYOBOSHI, WARERA TO SHUJO TO MINA TOMO NI BUTSUDO O JOZEN KOTO O.

“I hope this goodness will spread to everybody everywhere, so that we and living beings will all together realize the Buddha’s truth.”

Thursday, November 08, 2007

FU: Non-Insularity

This one character, the FU of FUKAN-ZAZENGI, has in itself very profound and great meaning. Even to have met just this one character, somewhere in a past life in between the cheating and lying, pimping and prostituting, wanking and worrying, I must have done something good.

Sometimes when I am in France (at time of writing I am back in England in pre-dawn insomnia mode) the sights or sounds or general energy of the forest sweeps away a surface layer of my habitual unenlightened concern with small matters -- for a while. That is my inspiration for discussing One Love (see also photo added to previous post), together with an email exchange with an old friend.

This old friend is the bloke who first shaved my head 20-odd years ago and revealed me in his words to be Cro Magnon Man. I called him a "stateless seeker of One Love." "Stateless" because though nominally American he went to school in the Middle East and in many ways he is more Japanese than American. And yet he is in no way Japanese. He is the person who taught me the fundamental rules of Japanese behaviour, while always demonstrating in masterly fashion how to skirt or flaunt those rules. "Seeker of One Love," partly because he has been a lifelong fan of brother Bob Marley, whom he knew for a time, not quite in a biblical sense, but in a very intimate way -- and he has the photos to prove it. But beyond the Rasta concept of One Love (which in itself might be of dubious universality rooted as it is in the old testament) Stateless Seeker looks for One Love in nature, and especially in the sea. "Everything goes in waves," he taught me, long before I had heard of the 2nd law of thermodynamics.

Stateless Seeker once described himself to me, in a phrase that stuck in my mind, as "just another nigger in the trenches." The phrase resonated with my own sense of coming from a downtrodden background. My mother, whose father ran away, was brought up mainly by her maternal grandparents, a cotton mill worker and a labourer in a Lancashire paint factory. My father was the son of a South Wales steelworker who in turn was the son of a poor Irish immigrant mother, Gran Cross, who after a coal mining accident in around 1910 was left a widow with an 11-year old son and seven younger siblings to bring up.

On the other hand, that 11-year-old grew up to be Sir Eugene Cross, a decorated war hero in WWI and leading light in the South Wales labour movement. And my parents were both bright sparks who went to grammar schools and ended up at Birmingham University where they met each other and -- at the very moment of losing their virginity to each other -- conceived yours truly, a big mistake from the very outset. By the time I was born on Christmas Day 1959 my 21-year-old father had been booted out of university and had got a job at the Austin factory at Longbridge. My memories of early childhood are coloured by Sundays in which the housekeeping money had run out and there was nothing in the pantry to eat. This may be why I continue to find it difficult not to be tight with money, and I worry about money, whether I have reason to do so or not. Sometimes I find it difficult to charge the going rate for professional work, and I charge people too little. Ironically, I charge them too little not because I don't care about money, but rather because I care about money too much. (A friend who worked in the city in Tokyo once told me that the guys who made the really big bucks were able to do so because they didn't care too much about money. They were thus able, with brass balls, to negotiate ridiculously big pay packets.)

Anyway, the point I am trying to make is that I came out of poverty, out of a long line of nobodies, but it was an educated or enlightened poverty out of which Uncle Eugene, a Big Somebody, Mr Ebbw Vale, had risen. And I ended up passing an exam to go to what was regarded as the posh school in Birmingham, where it was drilled into us that we belonged to a privileged elite. So all this is a kind of socio-economic attempt to excuse myself for being petty-minded, money-grubbing and elitist -- while at the same time having empathy for downtrodden underdogs everywhere.

Besides that, there is the cultural aspect, shared with other Brits and with Japanese too, of being brought up in an island nation. With that goes a similarly paradoxical combination of insularity, and irrepressible interest in the wider world.

Again, there is the religious/emotional aspect of having been brought up to believe in universal Christian values, and then enduring the shock of finding myself alone in Japan, bemusedly separated from my supposed soul-mate and living as a registered alien. Morever, for most of those years, through the economic bubble of the 1980s, the philosophy that was in the ascendancy in the Japanese media was NIHONJIN-RON, "Japanese-ism." When I attended Gudo Nishijima's Japanese lectures during the 80s, I would often hear him loudly singing out the words WARE-WARE. WARE-WARE this. WARE-WARE that. WARE-WARE simply means 'we,' but it very often appears in the nationalistic/racist context of WARE-WARE NIHONJIN, "we Japanese."

"Buddhism," Gudo would pontificate in English, "is an international religion."

No, you stupid so and so, the Buddha's teaching is not an -ism, and it is not an international religion. It is a universal teaching.

Is sitting-zen a gift to be bestowed from enlightened Japanese civilisation centred on practical, realistic doing, down to an unenlightened, barbarian world divided and ruled by the dualistic caucasian intellect?

No, it is not that.

If it is anything, it may be the true practice and experience, far beyond the bankrupt Rastafarian concept, of One Love.

It may be that when, through not taking too seriously the most serious thing in the world -- i.e., the inhibition of petty-mindedness, meanness, insularity, elitism, nationalism, racism, and all other forms of unenlightened behaviour -- a person truly realizes that One Love roundly pervades all, then the first thing which spontaneously expresses itself is universality.

Tuesday, November 06, 2007

Saturday, November 03, 2007

BODAI (4): Establishing the Mind

Alexander work, in a nutshell, is inhibiting unenlightened behaviour.

Anybody who has followed my progress on the blogosphere over the last couple of years may have concluded that I am not a particularly good advert for it.

What it entails, in any time that can be set aside just for work on the self, is taking some simple task -- say, rising from a chair, or moving a leg when lying down, or joining hands and bowing while sitting in lotus -- and watching oneself make more or less of a pig’s ear of it.

I have made a pig’s ear of a lot of things in my life, not least in key human relationships, but my relationship with Marjory Barlow was good in the beginning, middle, and end.

Practically the first words I heard Marjory speak were these: “Alexander work is supposed to be fun. It is the most serious thing in the world, this work, but you mustn’t take it seriously.”

Or to put it the other way, this work of inhibiting unenlightened behaviour is not to be taken seriously. BUT IT IS THE MOST SERIOUS THING IN THE WORLD.

Why? Because the original cause of suffering in the world is not out there in CO2 emissions and wars and floods and the rest of it. The original cause of suffering in the world is right here in me, in my views, opinions, expectations, in my habitual attitude of grim determination, in my wanting to feel secure, in my trying to be right, in my fear and greed, in my emotional worrying, in my endgaining and faulty sensory appreciation, in my susceptibility to be drawn into idle philosophical discussion, in my over-reliance on my top two inches, in my lack of practical wisdom; in short, in all my unenlightened behaviour.

The most serious thing in the world is my inhibition of my own unenlightened behaviour, and to see the most serious thing in the world as the most serious thing in the world, may be to establish the bodhi-mind.

Thus, to devote oneself just to sitting in the full lotus posture, with body, with mind, and as body and mind dropping off, is not selfish in an unhealthy way. It is, in Master Dogen’s teaching, the supreme way of establishing the will to cross all living beings over to the far shore of the Buddha’s enlightenment.

Anybody who has followed my progress on the blogosphere over the last couple of years may have concluded that I am not a particularly good advert for it.

What it entails, in any time that can be set aside just for work on the self, is taking some simple task -- say, rising from a chair, or moving a leg when lying down, or joining hands and bowing while sitting in lotus -- and watching oneself make more or less of a pig’s ear of it.

I have made a pig’s ear of a lot of things in my life, not least in key human relationships, but my relationship with Marjory Barlow was good in the beginning, middle, and end.

Practically the first words I heard Marjory speak were these: “Alexander work is supposed to be fun. It is the most serious thing in the world, this work, but you mustn’t take it seriously.”

Or to put it the other way, this work of inhibiting unenlightened behaviour is not to be taken seriously. BUT IT IS THE MOST SERIOUS THING IN THE WORLD.

Why? Because the original cause of suffering in the world is not out there in CO2 emissions and wars and floods and the rest of it. The original cause of suffering in the world is right here in me, in my views, opinions, expectations, in my habitual attitude of grim determination, in my wanting to feel secure, in my trying to be right, in my fear and greed, in my emotional worrying, in my endgaining and faulty sensory appreciation, in my susceptibility to be drawn into idle philosophical discussion, in my over-reliance on my top two inches, in my lack of practical wisdom; in short, in all my unenlightened behaviour.

The most serious thing in the world is my inhibition of my own unenlightened behaviour, and to see the most serious thing in the world as the most serious thing in the world, may be to establish the bodhi-mind.

Thus, to devote oneself just to sitting in the full lotus posture, with body, with mind, and as body and mind dropping off, is not selfish in an unhealthy way. It is, in Master Dogen’s teaching, the supreme way of establishing the will to cross all living beings over to the far shore of the Buddha’s enlightenment.

Friday, November 02, 2007

BODAI (3): Not That Attitude

The practice and experience that penetrates the Buddha’s enlightenment seems to demand of us that we drop off all habitual attitudes -- i.e., deep impediments to the emergence of our original features, that we pick up along the way generally unbeknowns to ourselves.

The subject of enlightenment is a difficult one. It seems to elicit particular reactions in people, depending on their own habitual attitude.

A typical religious attitude to enlightenment is to be in awe of it and to believe in it unquestioningly, suppressing all doubt -- at least until such time as suppressed doubt resurfaces.

The attitude of the true scientist is to seek the falsification of testable hypotheses. Insofar as the Buddha’s enlightenment is not testable, the scientific attitude towards the question of enlightenment is sceptical or disinterested.

An alternative attitude to enlightenment is the realistic attitude. I would like to give an example from my own experience of how a realistic attitude can help a person to be successful in life, not to be loser but to be a winner. In 1990 when my wife became pregnant with our first son, we had to move out of my small flat in Tokyo and look for a house out in the suburbs. We were looking at paying rent of Y100,000 (around £500) per month. Chie figured, based on the assumption that real estate prices in Japan would continue rising as usual, that we would be better off buying a house and repaying interest rather than paying rent. But by paying annual rent of Y1.2m on a house that was then valued at Y100m, I thought we were getting a good deal. The landladies who were expecting a yield on their investment of only 1.2% would be better off, it seemed to me, selling their overvalued asset. As things turned out, my recognition hit the target, and real estate prices in Japan bombed, leaving a huge hangover of negative equity. So nowadays whenever Chie and I disagree on something, I have an irritating habit of harping back triumphantly to this realistic decision made in 1990 to rent rather than to buy.

The realistic attitude, it seems to me, can be the attitude which is the most insidious and most difficult of all to shake off.

This morning while I was sitting with the door of my shed/dojo open to let in the sounds of the stream and birdsong, a wren hopped in and stood for a while, looking around, about two feet in front of my left knee.

If anybody knows of an attitude that causes the practice and experience of penetrating bodhi to get any better than that, this lucky loser would like to know about it.

The subject of enlightenment is a difficult one. It seems to elicit particular reactions in people, depending on their own habitual attitude.

A typical religious attitude to enlightenment is to be in awe of it and to believe in it unquestioningly, suppressing all doubt -- at least until such time as suppressed doubt resurfaces.

The attitude of the true scientist is to seek the falsification of testable hypotheses. Insofar as the Buddha’s enlightenment is not testable, the scientific attitude towards the question of enlightenment is sceptical or disinterested.

An alternative attitude to enlightenment is the realistic attitude. I would like to give an example from my own experience of how a realistic attitude can help a person to be successful in life, not to be loser but to be a winner. In 1990 when my wife became pregnant with our first son, we had to move out of my small flat in Tokyo and look for a house out in the suburbs. We were looking at paying rent of Y100,000 (around £500) per month. Chie figured, based on the assumption that real estate prices in Japan would continue rising as usual, that we would be better off buying a house and repaying interest rather than paying rent. But by paying annual rent of Y1.2m on a house that was then valued at Y100m, I thought we were getting a good deal. The landladies who were expecting a yield on their investment of only 1.2% would be better off, it seemed to me, selling their overvalued asset. As things turned out, my recognition hit the target, and real estate prices in Japan bombed, leaving a huge hangover of negative equity. So nowadays whenever Chie and I disagree on something, I have an irritating habit of harping back triumphantly to this realistic decision made in 1990 to rent rather than to buy.

The realistic attitude, it seems to me, can be the attitude which is the most insidious and most difficult of all to shake off.

This morning while I was sitting with the door of my shed/dojo open to let in the sounds of the stream and birdsong, a wren hopped in and stood for a while, looking around, about two feet in front of my left knee.

If anybody knows of an attitude that causes the practice and experience of penetrating bodhi to get any better than that, this lucky loser would like to know about it.

Thursday, November 01, 2007

BODAI (2): Do Not Doubt It!

Sitting-zen is the practice and experience that gets right to the top and bottom of the Buddha’s enlightenment.

And yet, the Buddha’s supreme and integral enlightenment, called anuttara-samyak-sambodhi in Sanskrit, is far beyond the likes of a grim-faced grasper like me.

That being so, there is a tendency in me, a very wrong disappointed tendency, when I grasp for the Buddha’s enlightenment as if it were a state-backed pension and thereby fail to get my grubby paws on it, to doubt whether it can ever be got.

If I say a word in my defense: Because I am at least aware of this tendency as the wrong tendency of a person who is not enlightened, I have never written a word on this blog that negates the existence of the Buddha’s enlightenment. At least I hope I haven’t.

Master Dogen’s teaching in Fukan-zazengi and in Shobogenzo, as I understand it, is neither that every dumb arse that presses down on a sitting-cushion is enlightened, nor that there is no such thing as enlightenment.

Rather, we who are not enlightened should establish the mind that is directed towards enlightenment, the bodhi-mind, primarily by devoting ourselves to the practice and experience that fully realizes the Buddha’s enlightenment -- that is, sitting-zen.

About 20 years Gudo Nishijima told me, “I got the enlightenment.” Since that time I have wobbled, not only backward and forward and from side to side but also up and down -- in the words of Pierre Turlur “like a yo-yo.” Was Gudo telling me the truth? Or was he lying to himself? Is he a fake? In suspecting that he is a fake elephant, am I doubting the real dragon?

But those questions do not arise from the bodhi-mind. Those questions arise from grim-faced grasping for my own security.

To establish the bodhi-mind is to resolve, beyond hesitation, disappointment or doubt, that because Gautama the Buddha got enlightenment I will keep making my effort, together with all living beings, to cross over -- primarily by devoting myself to sitting-zen.

And yet, the Buddha’s supreme and integral enlightenment, called anuttara-samyak-sambodhi in Sanskrit, is far beyond the likes of a grim-faced grasper like me.

That being so, there is a tendency in me, a very wrong disappointed tendency, when I grasp for the Buddha’s enlightenment as if it were a state-backed pension and thereby fail to get my grubby paws on it, to doubt whether it can ever be got.

If I say a word in my defense: Because I am at least aware of this tendency as the wrong tendency of a person who is not enlightened, I have never written a word on this blog that negates the existence of the Buddha’s enlightenment. At least I hope I haven’t.

Master Dogen’s teaching in Fukan-zazengi and in Shobogenzo, as I understand it, is neither that every dumb arse that presses down on a sitting-cushion is enlightened, nor that there is no such thing as enlightenment.

Rather, we who are not enlightened should establish the mind that is directed towards enlightenment, the bodhi-mind, primarily by devoting ourselves to the practice and experience that fully realizes the Buddha’s enlightenment -- that is, sitting-zen.

About 20 years Gudo Nishijima told me, “I got the enlightenment.” Since that time I have wobbled, not only backward and forward and from side to side but also up and down -- in the words of Pierre Turlur “like a yo-yo.” Was Gudo telling me the truth? Or was he lying to himself? Is he a fake? In suspecting that he is a fake elephant, am I doubting the real dragon?

But those questions do not arise from the bodhi-mind. Those questions arise from grim-faced grasping for my own security.

To establish the bodhi-mind is to resolve, beyond hesitation, disappointment or doubt, that because Gautama the Buddha got enlightenment I will keep making my effort, together with all living beings, to cross over -- primarily by devoting myself to sitting-zen.